A good programmer doesn’t get satisfied only with writing correct code, but concerning performance issues. In this post, I conduct some simple experiments to demonstrate how to make good use of cache in C++ to get better performance.

We have been taught in our C++ lesson that accessing a 2D array row-wise is faster than column-wise, which is because the array is stored row-wise (adjacent elements in row are stored adjacently in physical memory) and several conjuncted elements are read into cache at one time so that row-wise access will make good use of the cached elements. The more experiences with cache and memory in the Parallel Computing class this semester fires up my curiosity about how to write code with high performance, based on the knowledge of those cache and memory staff. This post contains experiments about some practical concerns for cache when writing code.

Row-wise v.s. Column-wise Array Access

Experiment runs on the following two code snippets:

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

{

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j)

{

sum += ary[i][j];

}

}for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j)

{

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

{

sum += ary[i][j];

}

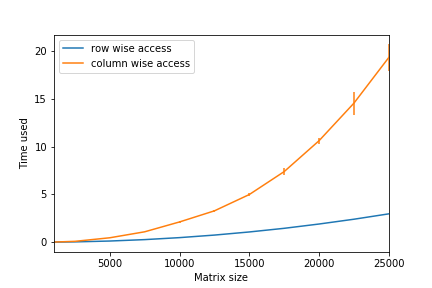

}I run the experiment 20 times and average their running time. Under g++-7 compiler, the result is given in the following figure.

|

This confirms our knowledge gained in class. But modern compilers usually allows you to turn the compiler optimization on. This adds up a -O option when using gcc or g++. The running time of the optimized program is interesting.

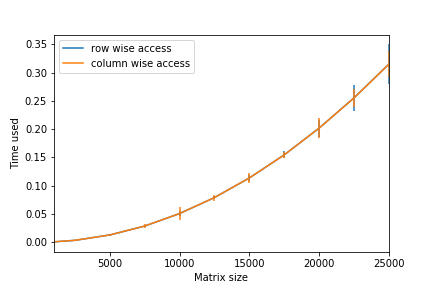

|

Not only faster, but the column-wise version is actually at the same performance with the row-wise one, which suggest that g++ is able to identify inefficient cache usage and fix it with primary level optimization.

Loop Tiling

Above is just a warm up. Let’s consider the matrix transposing problem. A naive approach is like this,

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j)

b[j][i] = a[i][j];However, when one of the matrix is accessed in row, another is bound to be accessed in column, which unavoidably violates our Row-Wise Access Golden Rule™. But if we can divide the array into several blocks that each fits into the cache, we will decrease the number of cache miss and boost the performance.

int bsize = 128;

for (int j1 = 0; j1 < n; j1+=bsize)

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i)

for (int j2 = 0; j2 < std::min(n-j1, bsize); ++j2)

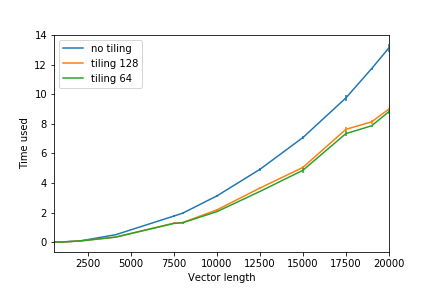

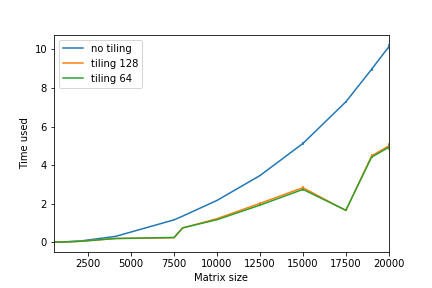

b[j1+j2][i] = a[i][j1+j2];We call this technique loop tiling. Comparing two code snippets in both non-optimized and optimized settings (where tiling 128 means bsize=128 and tiling 64 bsize = 64):

|

|

We can see that the implementation with loop tiling performs better than the non-tiling implementation.

If you want to figure out why

So why the tiling version runs faster? What does it mean saying “decrease the number of cache miss”? First we should understand the usage of cache.

What is cache and why we need it? When you are buying a computer, two of the most important parameters you should notice are CPU type(e.g. Intel core i5 or i7) and memory size (4G RAM, 8G RAM, etc.). When running a program, CPU is the device running instructions sequentially and memory is where data resides and the former fetches data needed for executing instructions from the latter. However, accessing the main memory is a relatively slow (high latency) process. But we can make some small but high speed device in between and store frequently used data in it so as to reduce the latency of data access. That device is called cache. Modern computers have several levels of caches and larger storage device tends to have higher latency.

|

Cache operation A cache is consisted of several cache lines. When data is migrating from main memory (or upper level cache) to cache (or lower level cache), conjuncted elements are fetched to fill in one cache line. Let’s see a real world example. On Ubuntu system, the information of your cache on each CPU resides in

/sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu{processer_id}/cache/index{cache_level}/Each index folder has several files in it (shown below), in which coherency_line_size tells the cache line size and size tells the total cache size.

coherency_line_size

physical_line_partition

size

level

shared_cpu_list

type

number_of_sets

shared_cpu_map

ways_of_associativityCache miss On my computer, the cache line size is 64 (unit: byte) and size is 32KB for level0 (index0) cache on any CPU. So for C++ int array (each element occupies 4 bytes), 16 elements are fetched into cache at a time, and there are totally 512 lines. So a block of 64x64 int array will occupy 256 cache lines, and two blocks filled the whole cache. We assume that in the beginning there is no data in the cache. When CPU runs b[0][0] = a[0][0], it queries the cache for a[0][0] and b[0][0] but cannot find them (we call this cache miss, which consequently cause the time consuming memory access operation), then elements a[0][0:16] and b[0][0:16] are fetched into the cache from main memory. Then when b[1][0] = a[0][1] is run, a[0][1] is already in the cache but b[1][0] not, so there is another cache miss and b[1][0:16] are fetched. When the whole cache is filled with data and new cache miss occurs, there would be some cache replacement policy to make space for new data.

For the experiment above, bsize=64 performs the best due to minimal number of cache misses for my machine (you can think of why), but the difference with bsize=128 is really small.

Other note

- I don’t know why in the optimized version there will be a drop around 17500. I’ll try the same experiment on other machine in the future.

- Hope there will be some OpenMP experiments in the future (if time permits).