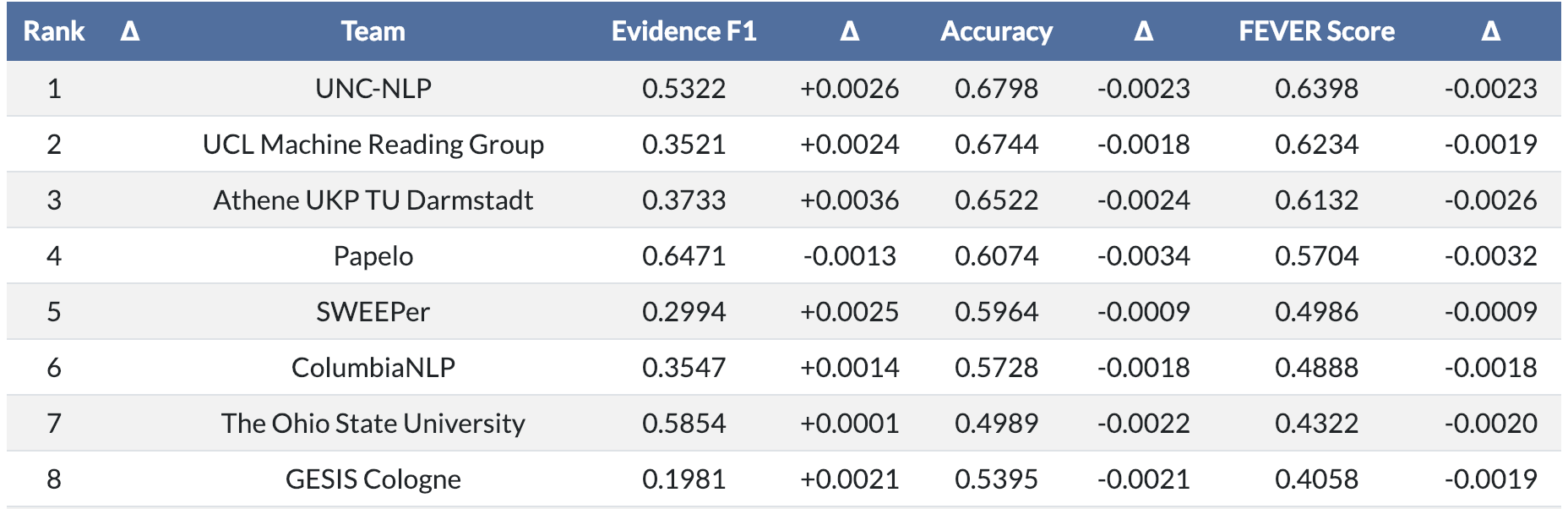

We are happy to announce that our team UNC-NLP (Yixin Nie, I and Prof. Mohit Bansal) got the first place in the recent FEVER Shared Task.

The objective of FEVER competition is to build a system that can automatically check a claim, e.g., “Berlin is the capital of German”, by searching relevant Wikipedia page (each page is called a document), finding supporting sentences (which is referred to as evidence) in the page and checking if the claim can be supported/refuted by these sentences. If no relevant information is found, the system should also notice that and report not enough info. We divide the process into three phases, namely, document retrieval (find relevant wiki page), sentence retrieval (find supporting sentence in the page) and claim verification (make final decision on supported/refuted/not enough info).

When building a machine learning system like this, the system often needs to learn from a large amount of data. The data is typically divided into three subsets, namely, training set, development (or validation) set and testing set. The training set is like homework for a student, where you give your answer, get the correct answer afterwards and learn from it. The development set, like an exam, is where you test your learned knowledge, and see how well you’ve learned. The testing set is like a real competition, where the best students are gathered (based on their score in the exam) and they compete with others world-wide. Back to the FEVER competition, these three subsets have different claims, but the task stays the same. The “answers” (which we refer to as ground truth) are provided to us for the training and development sets, which include the correct wiki pages, evidential sentences and final results (supported/refuted/not enough info). As for the testing set, only the organizer knows the correct answer. To give you a better sense, the sizes (total number of claims) for training/development/testing are around 150K/20K/20K respectively (K stands for thousand).

I build the document retrieval part of the system. The challenges here are: 1. You have to search the entire Wikipedia, which contains about 5 million pages; 2. To check a claim, you may need information from multiple documents and you should find them all. In this module, we extract keyword from the claim sentence and check if they can match any of the wiki page title. For example, for “Berlin is the capital of German”, you might want the page titled “Berlin”, in which, as you can check this wiki page, the first sentence support this claim (but for document retrieval we just aim at getting the correct page). However, the trick here is, there could be multiple titles with the same keyword. For example, there is actually a wiki page called “Berlin (band)”. This turns out to happen a lot and poses a great challenge to the system. To address this issue, we mainly (there is actually a whole bunch of heuristics) propose to use a metric called PageView. This metric is provided by those who maintain Wikipedia (thanks!), which indicates how often a page is viewed by different people. The intuition here is that if a page is visited more frequently, or say more popular, then it is more likely to be the correct page to support a claim. Here we assume that the claims in this competition also come from wiki pages that interest people most. As such, for our Berlin example, as Berlin has more PageView than Berlin (band), the former should be the correct answer.

I enter this competition largely by accident. At the time I was working on building a robotic system that can understand human instructions. It is an intersection area between natural language processing (NLP) and robotics, so it becomes part of my job to keep an eye on conferences in both NLP and robotics fields. I happened to encounter FEVER competition one day when I visited the EMNLP (shorthand of Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing) website. I found that the competition was closely related to Yixin’s research (he was mainly focused on natural language inference, which involves checking if two sentence support or refute each other), so we decided to give it a shot.

It seems that a system checking fake claims is not related to a robot understanding human instructions. Yet there could still be some relations. My research is specifically focus on endowing robot with commonsense knowledge in the interpretation of instructions. For example, given an instruction ``Pour some water to me’’, though the container to hold water is not specified, a human knows the water shall be poured into a cup. But for a robot without such knowledge, it might end up with pouring water to a book, a computer, etc. Interestingly, you can formalize this problem similar to a claim verification problem – if you can find more sentence to support “pour water to a cup” than “pour water to a book” (which hopefully is true), then the former might be a better choice.

Above is an example of the application our claim verification system on commonsense reasoning. This also reveals that the potential application field of our system is be very large, not just restricted to rejecting fake claims. Other possible applications include grouping equivalent questions on Quora or other question answering platform (i.e., when you compose a new question on Quora, find similar questions that have already been asked), open-domain question answering (answering a random question also requires finding relevant documents and sentences), etc.